Sage Agastya: The One Who Bent the Mountain

- A. Royden D'souza

- Nov 9, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 9, 2025

Middle-Late Treta Yuga (+ Vedic Rishi)

Vedic Account: Agastya begins not as a “character” but as a ṛṣi in the Veda, a poet-seer of Ṛgveda Maṇḍala. His origin myth is cosmic: Mitra and Varuṇa, gods of vow, law, oaths, behold the celestial Apsarā Urvaśī. A moment of desire flickers. Their semen spills.

The gods do not allow this divine seed to be wasted. So it is placed in an urn/pot (kumbha). From it emerge two powerful seers:

Vasiṣṭha (Brahma's mind-born son in the Puranas)

Agastya

Thus, in earliest strata:

Agastya is a child of cosmic vow-breach, but purified into radiance — a sage born of divine seed.

In the Veda he is a poet, a mantra-seer, not yet the man who drinks oceans. His words shape reality, that is his first identity.

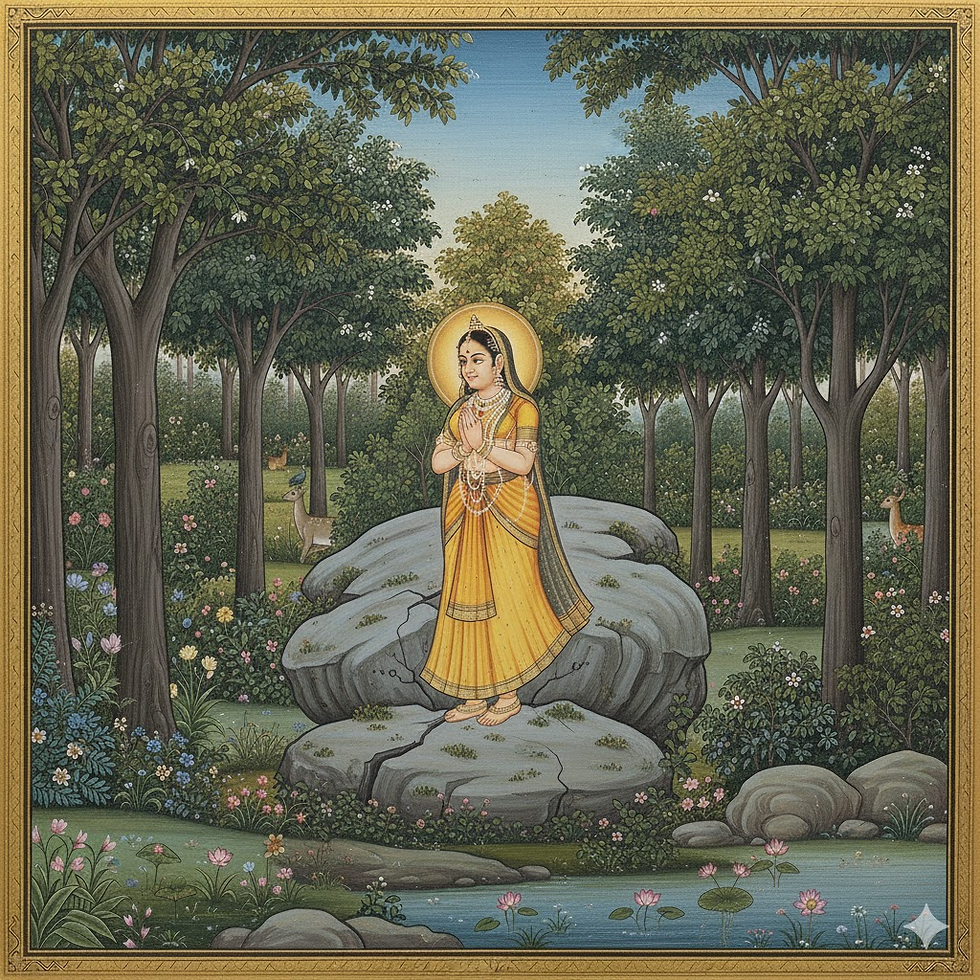

The Sage Who Fixes the World

In Brāhmaṇa literature, Agastya becomes a corrector of cosmic imbalance. He is invoked as a drafter of new alignments, the one who fixes what has gone wrong. He becomes, conceptually, the sage who restores order when the world-line jams. From this metaphysical role, later narrative will grow.

In the age of epics (Mahābhārata era), Agastya becomes embodied. He marries Lopāmudrā, a princess whom he literally shapes from virtues to suit his ascetic household. They have a son, Dṛḍhāsya (in some versions). Here we get the Agastya who performs tectonic corrections of the physical world.

Lopāmudrā is shown as his counterweight, the harmony to his intensity. Their dialogue is one of the most honest husband–wife conversations in Indian antiquity:

She asks for domestic fullness — love, wealth, physical union. He struggles between asceticism and duty. Agastya discovers what most sages fail to understand: renunciation that injures the home is also a form of imbalance.

Subduing the Vindhya

Agastya’s most elegant miracle is not violent, it is clever. Vindhya, the great southern mountain, begins to grow higher, broader, trying to eclipse the Himālayas and choke the sun’s path.

Agastya walks toward the south. Vindhya bows to allow him to pass.

Agastya says:

“Do not rise until I return.”

He never returns. Vindhya remains bowed forever.

The Slaughtering of Vatapi and Ilvala

There were two brothers, Ilvala and Vātāpi, experts in horrible hospitality. They were not just clever demons they were ritual murderers.

They targeted brāhmaṇas specifically because brāhmaṇas were carriers of sacred speech. Destroying a brāhmaṇa was a terrible sin.

Their method was a blasphemy of hospitality itself:

Vātāpi would take the form of a tender goat

Ilvala would cook him into fragrant meat

The guest would eat the meat without suspicion

Then Ilvala would call, “VĀTĀPI — COME FORTH!”

The demon, reforming inside the stomach, would explode outward, violence blooming from within

This was a reversal of creation. It was unbirth. Dozens of sages died this way, splintered from the inside.

When Agastya came into their hall, he came without fear. His presence turned the air heavy, as if the world itself was watching.

He ate the meat. He wiped his hand. He looked at Ilvala calmly.

Ilvala gave his customary signal:

“Vātāpi — COME!”

Agastya’s eyes did not even flicker. He spoke:

“Vātāpi — jīrṇo bhava.” [Be digested.]

And the demon was annihilated.

Agastya’s digestion, his internal fire, was more absolute than demonic resurrection.

It was a furnace no demon could escape.

Drinker of the Ocean

The war between the devas and the Kalakeyas had reached a strange paralysis. The asuras did not come out to fight. No spear could reach them. They had vanished into the folds of the sea’s belly, into caverns beneath the black salt water, where even sunlight was foreign.

The gods stood upon the shore, helpless, because courage means nothing against an enemy that refuses visibility.

Indra, for all his thunder, could do nothing. The ocean had become a shield of darkness.

When Agastya arrived, he did not ask for counsel. He just looked once at the horizon, and the waters seemed to tremble, as if they already recognized the force standing before them.

Then, without invocation, without battle-drum, he drank. Not symbolically. Not as a metaphor. He raised the ocean to his lips, and the waves and tides and hidden trenches poured inward, drawn by the gravity of his tapas, until the seabed lay naked and exposed like the skeleton of the first creation.

The Kalakeyas, those that had boasted: “No god can reach us here” — were suddenly bare to the sky.

And the devas fell upon them like the monsoon falls upon dry earth. When the slaughter was complete, and the air had the smell of iron and salt-ash, Indra spoke:

“Restore the waters, O Holy One.”

Agastya nodded, but the ocean returned only in part. Something of its vastness had been spent. Something of its primeval fullness remained inside the sage who had swallowed it.

And so, in certain old tellings, the sea’s present depth, the fact that it is “less” than it once was, is remembered as the imprint of Agastya’s act: a reminder that there once lived a man whose belly was wider than the world’s first ocean, and whose silence was more terrible than the thunder of the gods.

The Southward Journey

After humbling Vindhya, and leaving the mountain eternally bowed, Agastya did not return north. He kept walking.

He walked toward the land where the monsoon breathes differently, where the rivers twist like serpents, where the forests are not just vegetation but memory. He entered the region later called Tamilakam, a world of wet-green horizons and red earth that holds heat long after sunset.

And there, it is said, he did not merely preach, he planted. Not trees, but structure. Not buildings, but syntax. Language itself settled differently after Agastya’s arrival. Old Tamil tradition remembers him not as some wandering northern sage, but as a grammar-maker, the one who shaped sound into form, and tethered culture into speech.

He is recalled as:

a teacher of measure

a calibrator of order

one who brought the discipline of mantra to a land already rich in native gods, clan-spirits, and ancestral memory

Agastya did not erase the South, he interfaced with it. He brought Vedic fire into a landscape that already had its own flame. He became the hinge between two civilizational cultures.

And by his side, quietly, constantly, there is Lopāmudrā.

If Agastya is the one who moves mountains and empties oceans, Lopāmudrā is the one who stitches the home together so that such a man does not float away untethered. She is domestic gravity, the only force equal to his cosmic mobility. Without her, Agastya would be pure storm. With her, he is culture.

This is how Tamilkam remembers him: not merely as a visitor, but as one who helped bring civilizational continuity.

Sage Agastya Meets Rama

When Rāma wanders southward in exile, he comes to Agastya’s hermitage. The sage does not merely bless him, he arms him.

Agastya places in Rāma’s hands the bow once borne by Viṣṇu himself,and teaches him the invocation and restraint of divine astras, the very weapons that will one day strike Rāvaṇa.

Thus Agastya becomes the silent architect of the war to come, not by swinging a weapon, but by equipping the one who will.

The Cosmic Departure

There is no single, final scene of Agastya’s passing in the Veda. Great ṛṣis do not have a recorded moment of expiration. They do not collapse. They fade.

In southern memory, in the hills of Podhigai, it is said that Agastya simply withdrew. He went into the deeper forests, where the wind carries less language, where the mountains hold their breath, where the rivers are so old they no longer speak in syllables.

There, he sat. Not to perform a ritual. Not to chant for the world. Not to correct the axis of anything. He sat because his work was finished.

No thunder. No spectacle. No witness who could say, “I saw the moment.”

Tapas, the same inner fire that once digested Vātāpi and once held the ocean, simply consumed its own wick.

It is said in some Śaiva tellings that:

he dissolved into light near Podhigai’s blue-shadowed slopes

that his breath merged with the south

that the land itself took back the sage like a mother retrieving a child who finally slept

And this ending is suitable, because Agastya’s power was never about noise or display. It was correction. When correction is complete… there is nothing left to say.

Born from a vessel. Returned into formlessness. A perfect closing of the loop —the sage who once bent the world into balance exiting in utter, immaculate quiet.

References:

Vedic

Ṛgveda 1.165.9; 1.170–1.191 — Agastya hymns

Ṛgveda 7.33 (birth myth — Mitra/Varuṇa seed)

Taittirīya Brāhmaṇa 1.7.1 — Mitra–Varuṇa, Urvaśī episode

Epic/Puranic

Mahābhārata Vana Parva 96–100 (Vindhya episode)

Mahābhārata Udyoga Parva 5 (Ilvala–Vātāpi)

Mahābhārata Śānti Parva (Lopāmudrā dialogue hymn)

Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa, Araṇya Kāṇḍa 10–15 (Agastya + weapons to Rāma)

Brahmāṇḍa Purāṇa, Vāyu Purāṇa, Skanda Purāṇa — Agastya in Dakṣiṇa

Tamil Sangam tradition (Agattiyam attribution)

.png)

Comments